Tutoring

Handbook

Grades

K-8

Watauga County Schools

Appalachian

State University

Reich

College of Education

Boone,

North Carolina

Table of Contents

|

Getting Started

. |

1 |

|

Getting to Know Your

School

.. |

2 |

|

Getting to Know the Classroom

Teacher

.. |

2 |

|

Getting to Know the

Students

. |

3 |

|

Assessment

.. |

5 |

|

ASU Word Recognition

.. |

5 |

|

Spelling

. |

8 |

|

The Reading

Lesson

... |

10 |

|

The Phases of a Reading

Lesson

|

11 |

|

Directed Reading Thinking

Activity

.. |

12 |

|

Questioning

Strategies

|

28 |

|

Graphic

Organizers

. |

37 |

|

KWL

. |

38 |

|

Time Lines

.. |

39 |

|

Story Maps

. |

40 |

|

Diagrams

|

41 |

|

Character Maps

. |

42 |

|

Concept Maps

|

43 |

|

Venn Diagram

|

44 |

|

Sociogram

.

. |

45 |

|

Compare/Contrast Diagram

|

46 |

|

Discussion

Strategies

.. |

47 |

|

North Carolina End of Grade

Testing Information

|

50 |

|

Appendix

|

55 |

GETTING

STARTED

Getting Started

As we strive to improve the literacy levels of all students in all grades, the need for quality tutoring is growing. By working in coordination with the classroom teacher, tutors are a great resource in assisting children who are experiencing difficulty in the language arts program. In this chapter are tips to help you get started.

Getting to Know Your School

One way to become more comfortable with your tutoring environment is to take time to become familiar with the school. Some things to keep in mind as you get to know your school include:

q

Do I know the layout

of the school?

§

Make sure you know

where the office, cafeteria, media center, gym, and restrooms are located.

§

If a tour is not

provided, ask the teacher you are assisting if a student may give you a tour.

q

What do the different

bells mean? (fire drill, change of classes)

q

What are the procedures

for a fire? Tornado?

q

When I enter the

building where should I sign-in?

(Remember to sign-out when you are leaving school grounds.)

Getting to Know the Classroom Teacher

Once you have been assigned to work with a classroom teacher

you need to set up a time to meet with the teacher. This is a time for you to learn about the teacher and his/her

expectations of you. As a part of this

initial meeting, you will want to discuss the following:

q

Scheduling

§

Which days will I be

tutoring?

§

What are the times I

will be tutoring?

q

Students

§

What are the needs of

the students being tutored?

§

What are the goals of

tutoring sessions for these students?

§

You MUST maintain CONFIDENTIALITY about the students you are

tutoring. Discussions of students

should occur behind closed doors with the principal or the teacher with whom

you are working and always away from other students. Only at the discretion of the principal should you discuss the

progress of a student with anyone besides the classroom teacher.

q

Materials

§

Which materials will

I be using and where will they be located?

q

Place

§

Will I be working

within the classroom as an assistant?

§

Will I be working

with a small group in the class or in another location?

§

If I am not in the

classroom, where will I tutor? (in the library, in a conference room, etc.)

q

Class Rules - It is

important that a tutor have the same expectations for behavior as the classroom

teacher.

§

What are the behavior

expectations for the students?

§

What are the

consequences for not meeting behavior expectations?

q

Communication

§

How will you

communicate plans for the day to me? (notebook, folder, index cards)

§

How can we

communicate about tutoring sessions that will be the least disruptive to the

classroom? (notebook, folder, index

cards)

q

Absences

§

If I am unable to

make a tutoring session, what is the best way to notify the school?

Getting to Know Your Students

In the fourth through eighth grades most tutoring sessions

will be for small groups of 3 6 students.

Some things to remember about the students you are tutoring:

q

They realize they

struggle in reading and writing.

q

They may be

self-conscious about their learning difficulties.

q

They may be

embarrassed about needing special help.

q

They may cover up

their weakness with disruptive behaviors like clowning or excessive talking.

q

They may be upset

about being singled out or missing class.

Take some time, 5 10 minutes, to get to know your students at the first tutoring session. You may want to use the discussion guide at the end of this chapter to learn more about your students.

While

working with students it is important to:

q

Believe that ALL

students can learn.

q

Set high expectations

for student behavior and work.

q

Be friendly.

q

Be prepared. To minimize off-task behaviors have your

plans and materials ready.

q

Maintain classroom

rules and expectations.

q

Be positive. Provide students with praise for work accomplished

q

Be on time.

q

Follow the lesson

plans provided by the teacher.

q

Give clear and

specific instructions.

q

Give ample time for

student response.

q

Be encouraging.

GETTING TO KNOW EACH OTHER

Name:________________________________________________________________

Grade: __________Age:__________Teacher:________________________________

Family members I live with:_______________________________________________

Where I live:____________________________________________________________

Birthday:_______________________________________________________________

I have: Sister(s) Brother(s) No brothers

or sisters

My favorite music group:

My favorite singer:

My favorite subject in school:

My least favorite subject in school:

Three jobs I think might be interesting:

Interests and hobbies (Circle all

that apply. List others in the space

provided.)

Basketball Football Dance Fashion Cooking

Baseball Camping Hiking Tennis Cars

Music Shopping Art Games Soccer

I hope my tutor will

I am really good at

Two things I really like about myself are

ASSESSMENT

Some Title I tutors may be asked to conduct certain assessment items.

Assessment

One way to

assist teachers is to help with the assessment of certain skills. In this chapter directions for the ASU Word Recognition Assessment and the

Watauga County Spelling Assessment are provided.

It is important to remember:

·

that assessments are to only be given if requested by the teacher.

·

that the classroom teacher is responsible for interpreting the results of

the assessment .

·

the results of assessments are CONFIDENTIAL and only to be discussed with

the teacher.

ASU

Word Recognition Assessment

The

ASU Word Recognition Assessment is an individually administered test that

provides an estimate of the students instructional reading level. This information is used to determine where

to begin reading instruction. The test

measures word recognition ability in both a timed flash condition (1/4

second) and an untimed condition. Timed

scores indicate the students automatic sight word knowledge. Untimed scores indicate the students

decoding skill level. Individual

responses to words reveal phonic and structural skills.

DIRECTIONS

1. Before

beginning the assessment the teacher you are working with should identify the

approximate reading level of the students to be assessed. With the assistance of the reading teacher

determine which word list should be used to begin the assessment. Generally, the assessment would begin 2

levels below the approximate reading level.

|

Instructional

Level |

Beginning

Level for Word Recognition Assessment |

|

Below

1st |

PP |

|

1 |

PP |

|

2 |

P |

|

3 |

1 |

|

4 |

2 |

|

5 |

3 |

|

6 |

4 |

|

7 |

5 |

|

8 |

6 |

2. Words on the lists are flashed using stiff cards

to cover the words. Each word in turn

is flashed or exposed for approximately Ό of a second. If the response is correct, proceed to the

next word. If the response is

incorrect, separate the cards to expose the word and ask the child for another answer. After repeating the same word, or giving

another response or giving no response, move on to the next word.

3. If the student

fails to achieve a flash score of at least 80% of the words correct (16 words)

on the first list attempted, go to the next lowest level until a score of 80%

or more is achieved on the flash test.

4. Marking the

Score Sheet:

¨ Correct

responses on the flash receive no written mark.

¨ If the student

hesitates after the flash and then gives a correct answer before the word is

revealed again, mark an H in the flash column for hesitation and place a

check (4) in the untimed column.

¨ If the student

mispronounces or substitutes another word on the flash, write the actual

response in the flash column.

¨ If the student

does not provide a word in response to the flash, mark a 0 in the flash column.

If the correct response is then provided on the untimed presentation,

place a check (4) in the untimed column.

¨ If an

incorrect response is provided on the untimed presentation, write the response

in the untimed column. No response is

recorded as a 0.

EXAMPLE:

|

Level : 3rd |

Flash |

Untimed |

|

1. accept |

asset |

0 |

|

2. favor |

flavor |

4 |

|

3. seal |

|

|

|

4. buffalo |

H |

4 |

|

5. slipper |

0 |

sipper |

The example shows 4 incorrect responses in the flash column and 2 incorrect

responses in the untimed column.

5.

Stop the administration of the flash

test when the student misses 11 or more words in a list.

6.

Scoring

the test:

¨

Each

correct response represents 5%.

¨

To

score each level of the test, count the number of errors in the flash

column. Remember, hesitations count as errors in the flash column.

¨

For

each error, subtract 5 points from a possible score of 100. For example, 6 errors would give a flash

score of 70% of the words correct.

¨

To

figure the untimed score, count the number of checks (4) in the untimed column. For each check, add 5 points to the flash

score to arrive at the untimed score.

For example, a student who scores 70% on the flash portion and gives 4

correct responses on the untimed potion would have an untimed score of 90%.

7.

The

highest reading level at which the student scored no less that 60% on the

flash is the students predicted instructional reading level.

THE

READING

LESSON

Most

tutoring sessions in grades 4 8 will be in small group settings outside of

the classroom. During these sessions it

is important for students to have a structured lesson that focuses on the

skills the classroom teacher has outlined for the students. In this chapter the phases of a reading

lesson are given and then a strategy that incorporates the phases is described.

The Phases of a Reading Lesson

¨

The

pre-reading phase prepares students

to read the selection. This phase is a

time to get students interested in reading the selection, remind students of

things they already know that will help them understand the selection, and give

you an opportunity to pre-teach vocabulary or concepts that may be

difficult. Pre-reading activities and

questions give students a purpose for reading the selection. You may want to use organizational

structures to help students organize information they already know about a

topic.

¨

The

during reading phase is the actually

reading of the selection. This phase

may include silent reading, reading to students, or oral reading by

students. While students are reading

you may stop periodically to ask questions to check for comprehension.

¨

The post-reading

phase provides opportunities for students to organize information learned

from the text so that they can understand what they have read. Post-reading activities can be oral and/or

written. This phase provides an

opportunity to use organizational structures to help students organize their

understanding of the text.

Directed Reading Thinking Activities

A Directed Reading Thinking Activity (DRTA) incorporates

all three phases of the reading lesson.

A DRTA involves the tutor guiding the reading so the students are led to

interact with the story in an active problem-solving manner. DRTA's can be used with a variety of text (narrative

text, expository text, magazines, newspapers, etc.) When using a DRTA you will prepare students to read by asking

pre-reading questions. During reading

the students will silently read a small manageable part of the selection and

then orally answer comprehension questions, this process is repeated until the

selection is completed. After reading

students demonstrate their understanding of the selection through the use of an

organizational structure or through oral questioning.

The following pages provide the directions for writing a

Narrative DRTA, a planning sheet to help you include all aspects of a DRTA, and

a sample Narrative DRTA. Beside each question is a reference to the type of

question being asked if you are incorporating the Question Answer

Relationship to the DRTA. Refer to Page

30 for more information about question answer relationships (QAR).

Writing a Narrative Directed Reading Thinking Activity (DRTA)

1. Read the

story. As you are reading try to be aware of your thinking processes.

Are there

any potentially confusing passages?

At what points do you have enough

information to make a prediction?

Are there

any vocabulary words that need to be taught before reading or can the words be understood in

context?

2. Write

pre-reading questions.

Is there any background knowledge that

should be brought out?

What prediction question can be

asked based on the title and illustrations?

3. Pick stopping

points in the story based upon

- the amount of silent reading that the

students can handle at one time

-where the best prediction points

are found

4. Reread up to

the first stopping point. Write two to

four questions that bring

out the

central theme of the story.

Avoid questions that can be answered with

simply "yes" or no."

Ask both literal and inferential questions, such as Right There, Think

and Search, Author and You. (See

page 25)

Ask questions that require students

to locate evidence in the text.

Write a prediction question for the

next selection if appropriate.

5.

Reread

up to each stopping point and write questions. Questions may refer

back to previous predictions.

6. At the end of

the story write one-to-three discussion questions that deal with

issues

brought out in the story.

Is there an organizational structure that would help students better

understand the story?

Narrative Directed

Reading Thinking Activity Planning Sheet

Text:

Pages to be read:

Pre-reading:

Background

Questions/Graphic Organizer:

Vocabulary:

Stop 1

Questions:

Stop 2

Questions:

Stop 3

Questions:

Stop 4

Questions:

Post-Reading

Discussion

Questions / Graphic Organizer:

Sample

Narrative Directed Reading Thinking Activity

Text: Bridge to Terabithia by K. Patterson

Pages to be read:

Chapter 1, pp. 1-8

Pre-reading:

Background

Questions/Graphic Organizer:

Tell me about your best friend. What makes him or her so special?

Have you ever wanted to accomplish

something that would make you feel special? Explain.

Based on the title what do you think

this book is going to be about?

Explain.

*After the first

stop create a Family Tree Character Map.

Vocabulary:

Stop 1 page 2

Questions: (The

type of questions are noted in parenthesis, for explanation see page 25.)

Who is telling the

story? (AY)

Describe Jesse's

family? (TS) Draw a family tree to help

show relationships. You may want to include notes about each character as you

read.

Why is Jesse getting up early to run? (RT)

(P) Why do you

think winning was so important to Jesse?

Stop 2 page 5 paragraph

4

Questions:

Winning was

important to Jesse. Why? (TS)

What have you

learned about Jesse's father? (AY)

(P) Who do you

think will "start in on him" when he goes in the house?

Stop 3 page 8

Questions:

Who started in on

Jess when he came in? (TS)

What comments

were made to give Jess a hard time about running? (TS)

How would you

describe Ellie and Brenda? (AY) Use

proof from book and add information to family

tree.

What jobs will

Jess have to complete today? (TS)

(P) "He

thought later how peculiar it was that here was probably the biggest thing in

his life, and he had shrugged it off

as nothing." (p.8) What do you

think Jess is referring to? Why do you think it will "probably be the

biggest thing in his life?"

Post-Reading

Discussion

Questions / Graphic Organizer:

Add

information to the family tree.

Students could draw their own family

tree.

Are any of you the only boy or girl

in your family? Describe what that is

like?

Are you the youngest? oldest? or in

the middle? Describe your role in the

family?

Expository Directed Reading Thinking Activity

When you are using expository text (non-fiction

material) with students it is essential that you know the purpose for which you

are reading. Expository text can be

read for general information or for a specific purpose. If students are to read and understand how a

tornado forms, then your purpose for reading is specific; but if students are

reading to learn weather terms, then your purpose for reading is for general

information. Pages 15 - 19 provide the directions for writing an

Expository DRTA, a planning sheet, and two sample Expository DRTA's. (one is

reading for specific information and the other is reading for general

information ).

Writing an Expository Directed Reading Thinking Activity

1. Determine the

purpose for reading the text.

Is the reading to develop general

knowledge of a topic or is there specific information

you want the student to read for?

2. Read the part

of the text that meets your purpose. As

you read try to be

aware of

your thinking processes.

Are there any vocabulary words that

need to be taught before reading or can

the words be understood in context?

At which points is more

clarification needed?

At which points do you have enough

information for a discussion?

3. Plan the

pre-reading.

Is there an organizational structure that will help focus the students on

the topic?

What background knowledge should be

brought out?

Which vocabulary should be taught

before reading? How will it be taught?

4. Choose

stopping points in the text based on

where the best discussion points are found

where clarification will be needed

the amount of silent reading that

students can handle at one time

5. Reread to the

first stopping point. Write two to four

questions that focus on

the purpose

of the reading. Stopping points may

occur after one or two

paragraphs

instead of entire pages.

Avoid questions that may be answered with

simply "yes" or "no"

Ask literal and inferential

questions (Right There, Think and Search, Author

and You)

Ask questions that require students

to locate evidence from the text

Look ahead and write 1 or 2

prediction questions.

6. Reread to

each stopping point and write questions.

7. At the end of

the selection ask discussion questions that deal with the content

of the

passage and/or use a graphic organizer to help the student understand

the

information.

Can the material be organized sequentially,

in a hierarchy, through an illustration,

by showing a relationship, or by comparing and contrasting?

Expository Directed

Reading Thinking Activity Planning Sheet

Purpose for

reading:

Text:

Pages to be read:

Pre-reading:

Background

Questions/Graphic Organizer:

Vocabulary:

Stop 1

Questions:

Stop 2

Questions:

Stop 3

Questions:

Stop 4

Questions:

Post-Reading

Discussion

Questions / Graphic Organizer:

Expository Directed Reading Thinking

Activity Sample #1

Purpose for

reading:

Sponges- where they live, how it

lives, how they look (color, shape, size)

Text: Incredible

Facts about the Ocean

Pages to be read:

pp.69-74

Pre-reading:

Background

Questions/Graphic Organizer:

Use KWL chart (see page 32) as a

group

What do you KNOW about sponges?

What do you WANT to know?

Vocabulary:

Stop 1 paragraph 1

Questions:

Where can sponges

by found? (TS)

What type of

sponges are sold in stores? (RT)

(P) How do you

think a sponge eats?

Stop 2 top of page 72

Questions:

How is a sponge

different from most animals? (RT)

What must a

sponge have to stay alive? (RT)

Describe how

water travels through a sponge. (TS)

What is another

word for holes in the skin? (RT)

What do you a

sponge looks like? (Own Your Own)

Stop 3 page 74

Questions:

What sizes do

sponges come in? (TS)

Describe the

color of sponges I might see. (TS)

Compare and

contrast the shapes of sponges. (TS)

Post-Reading

Discussion

Questions / Graphic Organizer:

Finish KWL. What have you LEARNED

about sponges?

Illustration (sequential):How water

travels through a sponge, label the parts of the sponge

Expository Directed

Reading Thinking Activity Sample #2

Purpose for

reading:

Learn landform terms associated with

the ocean

Text: Incredible

Facts About the Ocean

Pages to be read:

Chapter 1 (pp. 11-32)

Pre-reading:

Background

Questions/Graphic Organizer:

Brainstorm a list of landforms

Categorize the list (concept map)

into where the landforms are found (LAND or WATER)

Vocabulary:

Stop 1 page 11

Questions:

Define a

continent. (RT)

Why are there

more continents that continental land masses? (TS)

Give an example

of a peninsula. (RT/TS)

Describe what a

peninsula looks like. (RT)

(P) What are some

ways the author can help you understand information?

Stop 2 page 14

Questions:

What information

can we learn from the table? (RT)

How did the

author organize the information to help you compare the continents? (AY)

Which continent

has the most square miles? (RT)

Which continent

has the least square kilometers? (RT)

Which continents

are surrounded by four different bodies of water?

(P) Which island

do you think is the largest in the world?

Stop 3 page 17

Questions:

What is important

to know about words in bold type? (RT)

Describe the

difference between an isthmus and a cape. (TS)

How is an island

different from a continent? (RT)

Of the 10 largest

islands which ocean has the most islands? (TS)

(P) How do you

think islands are formed?

Stop 4 page 20

Questions:

Describe the

formation of an island. (Ask 3

students, each must tell a different way) (RT/TS)

(Students could

each choose a formation to illustrate and label)

(P) What do you

think an atoll is ? Where do you think

it is located?

Stop 5 page 24

Questions:

Where are most

atolls found? (RT)

Using the

pictures on page 23 describe the formation of an atoll? (TS)

(P) Explain how

you think a delta is formed?

Stop 6 page 27

Questions:

Where are deltas

found? (RT)

How are they

formed? (RT)

Explain why you

think the experiment is similar to how a delta is formed. (TS/AY)

(P) Tell me what

you know about sand.

Stop 7 page 30

Questions:

When can a

sandbar be seen? (RT)

How can I locate

a sandbar I cannot see? (RT)

Why are there

different colors of sand? (TS)

(P) What does the

word seashore make you think about?

Stop 8 p. 32

Describe a

seashore. (RT)

Other than sand

what else could a beach be made of ? (TS)

Post-Reading

Discussion

Questions / Graphic Organizer:

Add to the

concept map.

Divide WATER

landforms into two categories: Connected to Land and Not Connected to Land

K‑W‑L

1. The teacher chooses an appropriate topic

and text.

2. The teacher introduces the K‑W‑L

worksheet (see Figure)

3. The students brainstorm ideas about the

topic.

4. The teacher writes this information on a

chart or chalkboard.

5. Students write what they know under the K

("What I know") column.

6. Together, the teacher and students

categorize the K column,

7. Students generate questions they would like answered about

the topic and write them in the W ("What I want to learn") column.

8. Students silently read the text and add

new questions to the W column.

8. After reading the selection, students complete the L

("What I learned")

column.

9. The students and teacher review the K‑W‑L sheet

to tie together what

students knew and the questions they had

with what they learned.

Echo reading

1.

The teacher selects a

text around 200 works long that is near frustration level reading for the

student.

2. The teacher reads the first line of the text, accentuating appropriate phrasing and intonation.

3.

Immediately, the

student reads the same line, modeling the teacher's

example.

4. The teacher and the

student read in echo fashion for the entire passage,

increasing the amount of text when the

student can imitate the model.

Retelling

1.

Before reading, the

teacher explains to the students that he is going to ask them to retell the

story when they have finished reading.

2.

If the teacher is

expecting the students to include specific information, he should tell the

students before reading.

3.

The teacher asks the

students to retell the story as if they were telling it to a friend who has

never heard it before.

4. The students tell the story.

5. If the student hesitates, the teacher can

prompt.

6. When the retelling is complete, the teacher can ask direct

questions about important information omitted.

Teaching Strategies for classroom and tutoring

Strategy Instruction

1. The teacher selects the new procedure to be learned.

2. The teacher talks about the strategy, what it is like, and

gives some

examples.

3. The teacher explains why the strategy works when reading.

4. The teacher models the new strategy in authentic texts. This

means he talks about how he reads the text, paying particular attention to the

targeted strategy.

5. The students use the targeted strategy in authentic texts.

They talk out loud

about their problem-solving strategies.

6. The teacher supports the strategic thinking of the

readers. He phases it in to

coach thinking and phases it out to let

students use and discuss the

strategies they used for they text

interpretation.

7. Students are asked to assess their strategy deployment and how it affected

their text interpretation.

8. The teacher explains when to use the strategy and what to do

if its use is not

effective.

Graphic

Organizers

1. The teacher chooses a chapter from the text book.

2. The teacher selects key vocabulary words and concepts.

3. The teacher arranges the key words into a diagram that shows

how the key words interrelate.

4. The teacher adds a few familiar words to the diagram so

students can connect their prior knowledge with the new information.

5. The teacher presents the graphic organizer on the chalkboard

or the overhead transparency. As he presents the organizer, he explains the

relationships.

6. Students are encouraged to explain how they think the

information is related.

7. The students read the chapter, referring to as needed, the

graphic organizer.

8. After reading the selection, the students may return to the

graphic organizer to clarify and elaborate concepts.

Reciprocal Teaching

1. The teacher selects a text from the content area.

2. The teacher explains the four tasks a) question generating,

b) summarizing, c) clarifying the difficult parts, and d) predicting what the

next section will discuss.

3. Both the teacher and the student silently read the first

section of the text.

4. The teacher talks about the four tasks of reading for that

section: a) He constructs several good questions, b) he constructs a summary of

the section, using the main idea and supporting details, c) he clarifies

difficult parts by stressing the vocabulary an organization, and d) he predicts

what the next session will discuss by using the title and headings.

5. The students help revise the summary, answer the question,

clarify unclear parts of the summary and the text, and evaluate the prediction

(agree or disagree and give a reason for doing so).

6. After a few models by the teacher, the student takes the

role of teacher. She thinks aloud, using the four steps.

7. The teacher becomes a student and assumes the students

role.

8. Students take turn playing teacher.

9. Periodically the teacher reviews the four activities with

the students.

10. As the students play teacher, the teacher provides feedback

and encouragement.

From Lepper, M. R.,

Woolverton, M., Mumme, D.L., & Gurtner, J. (1993). Motivational techniques

of expert human tutors: Lessons for design of computer based tutors. In S. P.

Lajoie & S.J. Derry (Eds.), Computers as cognitive tools, pp75-105.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Four Motivational Goals of Successful Human Tutors

1.

To enhance the

learners level of confidence or self-efficacy.

2.

To produce an

appropriate level of challenge for the learner.

3.

To maintain in the

learner a sense of personal control.

4.

To elicit from the

learner a high level of curiosity.

Strategies for Enhancing Confidence and Challenge

I Maintain

a sense of challenge

A.

Modulate object task

difficulty

1. Select appropriately difficult problems for

the students

a. Proceed generally

from easier to harder problems as a students

skills

increase.

b. Modulate the difficulty level of individual problems as a

function of

the students current level of

understanding.

2. Provide scaffolding for the student.

a. Decide whether, when, and how to intervene in problem

solving to

forestall or to correct errors.

b. Breakdown the problem so as to decrease the size of the

steps

required

for successful problem solutions.

c. Increase or decrease the specificity of hints provided to

the student as a function of the students difficulty at a particular point.

B.

Modulate subjective

task difficulty

1. Emphasize the difficulty of the task.

2. Challenge the student directly.

3. Engage in playful competition with students.

II Bolster Self Confidence

A. Maximize success

1. Praise the student after success.

2. Express confidence in the student after success

3. Comment on the difficulty of the task before or after

success

4. Emphasize student agency after success, portray the student

as an independent problem solver.

5. Engage in playful competition with the student after the

student has been successful.

B. Minimize failure

1. Reassure and commiserate with the student after failure.

2. Redefine success vs. failure (emphasize partial success).

3. Comment on the difficulty of the task.

4. Discuss explanations for causes of student failure.

5. Provide indirect feedback (ask questions, provide hints

rather than explicitly label an answer incorrect).

Strategies for Enhancing Curiosity and Control

I. Evoke

Curiosity

A. Make us of the Socratic methods

1. Select problems that themselves pose, or will later permit

the tutor to

ask leading questions.

2. Ask telling questions regarding problem solution, requiring

further

thought or articulation following

successful performance( How did you

figure that out).

B.

Make use of

Associative methods

1. Present problems in real contexts that show how the

knowledge being

taught

might be put to use by people whom the student knows, likes, or respects.

2. Present problems in fantasy contexts that allow students to identify

with

popular characters or interesting situations.

II.

Promote a Sense of Personal Control

A. Increase objective control

1. Offer real choices in situations in which the tutor is not

certain what

would be best for the student

(additional help, using a particular

strategy, moving to harder problems).

2. Offer instructionally relevant choices (pen/pencil, color of

paper,

manipulatives, character names).

3. Allow students to offer their own ideas and suggestions and

comply

with reasonable ones.

4. Transfer control physically from the tutor to the child

(turning

pages, writing).

B. Increase subjective

control

1.

Use of indirect

feedback style (ask questions and provide hints

rather than give answers).

2.

Create situations

that provide opportunities for student control.

3.

Emphasize overtly the

students own agency in the situation.

QUESTIONING

STRATEGIES

Questioning Strategies

One of the important elements of a reading lesson is the

level of questioning that is provided by the tutor. Research has shown there

are different levels of thinking and the questions we ask reflect the level of

thinking required of students. Below is

a list of the thinking skills from the simplest to the more complex:

·

Knowledge: Knowledge can be declarative (attributes, rules) or procedural

(skills and processes). Items of this

type are factual, content-specific, and focus on recall of critical

information, concepts, and procedures.

·

Sample Questions:

·

When

was ______?

·

Who

did it ______?

·

What

is a ______?

·

Identify the ______ in the _____.

·

Who

is the narrator of the story?

·

Organizing: Organizing

is used to arrange information so it can be understood or presented more

effectively.

·

Sample Questions:

·

What

do the characters have in common?

·

What

conclusion have you reached about ________?

·

What

traits best describe the hero in the story?

·

Describe

Tell how

Compare

·

Explain

why ________ ?

·

Applying: Applying

is used to demonstrate prior knowledge within a new situation. The task is to bring together the

appropriate information, generalizations or principles that are required to

solve a problem.

·

Sample Questions:

·

What

evidence is there that _____?

·

Which

of these would _____?

·

How

would you use this information for yourself _____?

·

Analyzing: Analyzing

is used to clarify existing information by examining parts and relationships.

·

Sample Questions:

·

What

part of this could be real?

Make-believe?

·

What

would be a good title for ____?

·

Sort

the ________.

·

Compare

_________ to ________. How are they

alike? Different?

·

What

is the order of the steps in _____?

·

Generating: Generating

involves prior knowledge to add information beyond what is given.

·

Sample Questions:

·

If

you had been ______ what would you have done differently?

·

How

many ways can you think of to ____?

·

What

would happen if ____?

·

Predict

what would be true if ____?

·

How

can you explain

?

·

Hypothesize

what would happen if ____?

·

Integrating: Integrating

involves putting together the relevant parts or aspects of a solution,

understanding, principle, or composition.

·

Sample Questions:

·

How

many ways can you think of to ____?

·

Summarize

the story in your own words.

·

Devise

a plan to _____?

·

Evaluating: Evaluating

involves assessing the reasonableness and quality of ideas.

·

Sample Questions:

·

Should

_______ be permitted to ______? Why or

why not?

·

Judge

what would be the best way to _________.

·

Was

it right or wrong for _____? Explain.

·

What

is the most important? Why?

·

What

could have been different?

As you prepare questions to use with the students you

are tutoring, it is important to stretch student thinking and ask questions

that require more than yes or no responses. If students are only answering questions that require little

interpretation of the text, then they will continue to only answer questions at

that level.

The remainder of this chapter provides you with a

strategy for helping students understand the relationship between questions and

answers and sample questions for you to refer to as you prepare your lesson.

Question-Answer Relationships (QAR)

Students that understand how questions are written do a

better job answering questions than students who lack this understanding. It is important to teach students about

question-answer relationships. There

are two broad categories of questions: In

the Book and In My Head.

There are two types of In the Book questions: Right

There and Think and Search. Right

There questions can be answered from one place in the selection. Tell the students if they can put their

finger in one place in the book to answer the question, it is a Right There question. Think

and Search questions involve looking in more than one place in a selection

for an answer. If it takes more than

one finger to point to the answer, it is a Think

and Search question.

In My Head questions are divided into two

categories: Author and You and On My Own. Author and You

questions require students to think about what they have read. The answer is not found in the

selection. Students use what they know

on their own along with the information gained from reading. On My

Own questions can be answered without reading the selection. When answering On My Own questions students must provide support for their answer

from their own experiences and background.

QAR's can be incorporated with any reading material

(i.e., magazines, poetry, narratives, expository text, textbooks, etc.). After teaching the four types of questions

and using them to discuss text, begin allowing students to write their own questions

for discussions. The questions asked

should have students refer to the text for evidence to support their answer,

and the wording of questions should be varied and require students to think

about what is being asked.

The following pages give you a visual

representation of Question-Answer Relationships. You may use this to make a poster for your students or to copy

and give to students.

QUESTIONS

which elicit higher-level thinking

1.

How

does this _______ compare with . . .?

2.

What

are some of the reasons why . . .?

3.

What

do you think caused . . .?

4.

What

are some other examples of . . .?

5.

Is

this _____ like anything from your own experience . . .?

6.

What

will happen if . . .?

7.

How

would things have changed if . . .?

8.

Since

this is true, what else can we conclude . . .?

9.

If

you were . . .?

10.

Can

you think of a new way to . . .?

11.

What

are some questions you might ask . . .?

12.

How

does that differ from . . .?

13.

What

is most important about . . .?

14.

What

would you like to know about . . .?

15.

Have

you ever felt . . .?

TEACHER RESPONSES to student answers

1.

Explain

what you mean by . . .

2.

Tell

me more about . . .

3.

Expand

on that idea . . .

4.

How

does that fit with what ______ said . . .

5.

I

hear you saying . . .

6.

What

makes me think of . . .

7.

Does

anyone want to speak to ______ about . . .

8.

So

what conclusions can you draw from . . .

9.

What

else . . .

10.

Could

be, yes, an interesting idea . . .

11.

I

wonder what______ would say about . . .

12.

Can

someone else tell me what ______ is saying about . . .

13.

Ive

never thought of it in that way before . . .

14.

Tell

me more about that word . . .

15.

Can

you convince me that . . .

North Carolina Testing Terms Glossary

ASSESSMENT FORMATS

Multiple Choice an

assessment format in which the student is asked to choose from a list of

possible options the one correct or the one best response to the given question

Free Response an

assessment format in which the student is asked to create a written response of

the one correct answer to the given question

Open-Ended an

assessment format in which the student is asked to create a written response,

where the correct response may vary there is not simply one correct answer or

there is more that one strategy for arriving at the answer

Performance an

assessment format in which the student is asked to apply knowledge and skills,

actively; an assessment task that requires the student to create an answer or

product to demonstrate his or her knowledge or skills

TERMS USED IN TEST ITEMS

DIRECTIONS/SKILLS

Analyze to

separate into elemental parts or basic principles so as to determine the nature

of the whole

Apply to

bring together relevant information from one situation and transfer it to

another similar and appropriate situation

Assume to

take upon oneself; to adopt

Affect to

influence the reader or cause a particular response in the reader

Compare to

appraise with respect to similarities and differences with the emphasis on

similarities

Contrast to

appraise with respect to differences

Convey to

impart or communicate by statement, suggestion, gesture, or appearance

Convince to

persuade to a viewpoint based upon specific references to the passage

Describe to

respond to a question or statement by representing or giving an account, which

is expressed in words, in order to produce a mental image, for the reader, of

something observed or experienced by the writer

Elaborate to

add details, explanations, examples, or other relevant information to improve

understanding

Evaluate to

assess or judge the reasonableness and quality of ideas or concepts

Explain to

respond to questions; to give ones viewpoint; to defend that viewpoint through

a logical progression of ideas that includes citing appropriate, specific

examples

Imagine/

Pretend to

form a notion or idea about something

Impression a

telling image or feeling produced on the senses or the mind

Infer to

go beyond the available information to identify, describe, or discuss what may

reasonably be true

Justify to

defend a response using specific examples and references

Predict to

estimate future behavior or events based upon present and past information,

i.e., likely happen, probably happen

React to give a response

Reference to cite specific information from a passage to support a

viewpoint

Represent/

Show/Model to

symbolize or change the form, but not the substance, of the information

Summarize to

combine information efficiently and succinctly into a cohesive statement

(involves condensing information, selecting what is important and discarding

what is not)

EVALUATION TERMS

Approximately/

About almost

the same as, close to, but not equal to, i.e., used in estimation items in

mathematics

Best an

evaluative term meaning exceeding all others in terms of quality and

correctness

Except with

the exclusion of; but; to leave out; except

Least an

evaluative term meaning lowest in rank or importance; meaning smallest in

degree or magnitude

Mainly an

evaluative term meaning greatest in number, quantity, size, or degree; in the

highest degree, quantity, or extent

Most an

evaluative term meaning the principal or most important part of point

OTHER TERMS

Details individual

parts of a whole; details add substance to a response

Evidence information

and details presented in a given passage

Example an

instance that serves to illustrate; a part of something taken to show the characteristics

of the whole

Fact that

which can be observed or verified; objective

Feature a

characteristic of a passage

Illustration a

picture or drawing

Opinion a

belief or idea held with confidence but not substantiated with direct proof or

knowledge

Passage a

piece of material, such as a story, poem, recipe, graph, cartoon, blurb,

excerpt

GRAPHIC

ORGANIZERS

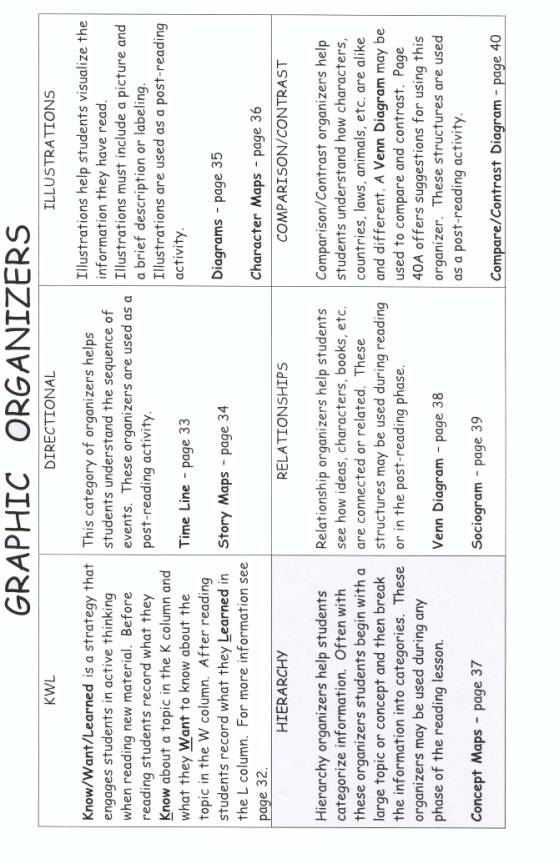

Graphic Organizers

One way to improve a students literacy level is to

develop his/her understanding of the text being read. Oral and written questioning strategies are one way to check for

comprehension of the text. Another

strategy to help students understand the information they have read is to use

graphic organizers. There are 6 categories of graphic organizers: KWL,

Directional, Illustrations, Hierarchy, Relationships, and

Comparison/Contrast. A description of

the categories and references to specific graphic organizers in that category

is provided on the chart on the next page.

Graphic Organizers:

Are tools students and teachers use to

establish organization patterns for their thinking, writing, discussions, and

reporting.

Provide structure for recording

information, ideas, or options.

Make the content visual to learners.

Help students remember because the graphic

organizer becomes a map that makes abstract ideas more visible and concrete

Bridge the connection between prior

knowledge, what the student is doing today, and what they can apply and

transfer to other things.

Graphic organizers should align with the purpose of the

assignment and the skill you are reinforcing.

For example, if a student has difficulty understanding the sequence of

events in a narrative, then a story plan, which is a directional graphic

organizer, should be used.

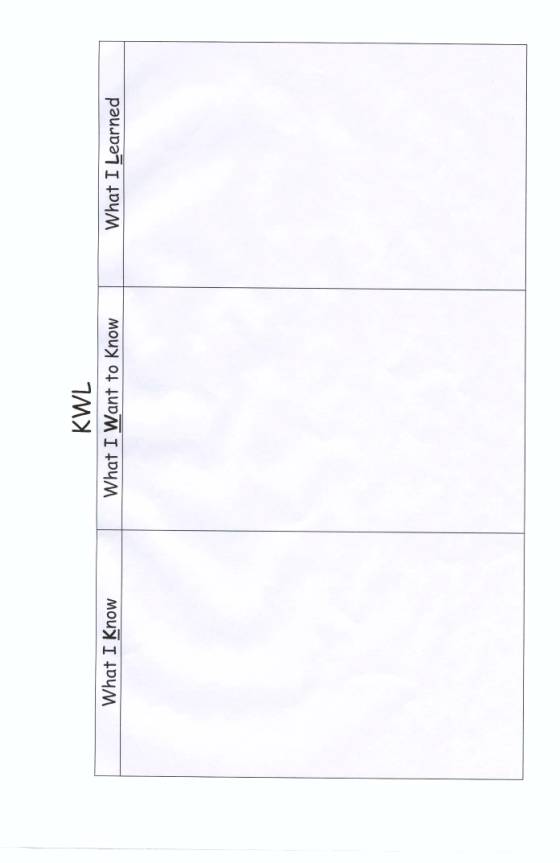

KNOW / WANT / LEARNED (KWL)

Know / Want

/ Learned

is a strategy that models the active thinking needed when reading new material

or participating in a learning activity.

It encourages the student to think about ideas and to ask questions while

reading. The letters KWL represent what students KNOW about a topic, what they WANT to find out or learn, and what

they LEARNED as they read. The strategy is a five-step process that may

be used across the curriculum, at all grade levels, with any size group or with

a whole class.

Step 1

Preparation:

The teacher determines a key concept for the material to be studied.

Step 2

Group Instruction: Students brainstorm what they already KNOW about the topic and try to create general categories as two or

more pieces of information grouped together under a category. The teacher models the thinking-aloud

process while identifying, combining, and categorizing information. The teacher asks students to think about the

categories of information they would expect to find, and these are listed so

that students see them.

Step 3

Individual Questions: Individual students record what they feel confident they KNOW about the concept under What I Know on the KWL Chart. Under What I Want to Find Out, students list

questions or information they might want to learn. Students are encouraged to generate questions from information

gleaned as they brainstormed and as they read.

Step 4

Reading the Text: The text should be divided into manageable segments based on the

students needs and abilities. Some

students may be able to read only one or two paragraphs. The intent is for the student to monitor

comprehension by referring to the questions listed. In this way, students become aware of what they learn. They should jot down the answers to their

questions as well as new questions under What I Learned.

|

K What I Know |

W What I Want to find Out |

L- What I Learned |

|

Had ceremonies Ate berries Lived in America Lived in teepees Hunted Made canoes |

Did Indians live in one place? Did they use stone tools? Did they domesticate the dog? Did they believe in spirits? How did they make pottery? |

Many different tribes in America Used different kinds of tools Rode horses, had dogs Cooked many dishes Lived off the land Had sophisticated religion |

Step 5

Reflection: Engage

the students in a discussion about what they learned from reading. When all questions have been answered, the

students summary of the material may be a starting point for a writing

assignment.

A blank KWL

chart is provided in the Appendix.

Boysen, Commissioner Thomas C., Transformations: Kentuckys Curriculum Framework. Pages 114-115. 1993. Frankfort, Kentucky: Kentucky Department of

Education.

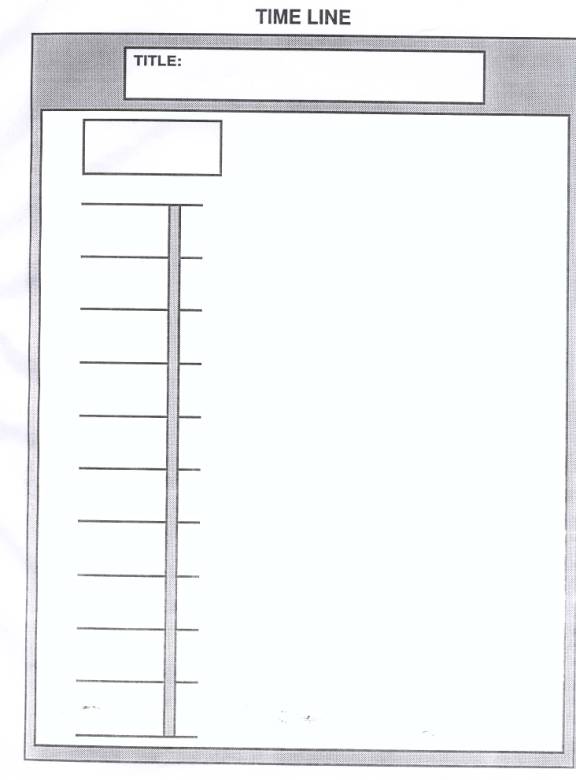

Time Lines

Time Lines may be used with fiction and non-fiction

text. When reading fiction a timeline

may be used to record the events of the day or the week. If the story covers a longer period of time

monthly events may be recorded. For

example, if you are reading The Flunking

of Joshua T. Bates you could use a time line to record the events of a day

at school.

Non-fiction materials, such as, biographies or autobiographies, are easily adapted to time lines. As events occur in a person's life specific dates can be recorded.

When using a timeline it is important to have students

record when the event happened and give a brief description of the event. Pictures may be a part of the

description. You may want to complete a

part of the timeline after reading each chapter or several chapters, instead of

waiting to complete the book.

A blank time line is provided in the Appendix.

Parks, S. and H. Black.

Organizing Thinking. Pacific Grove, CA: Critical Thinking Press

and Software, 1992.

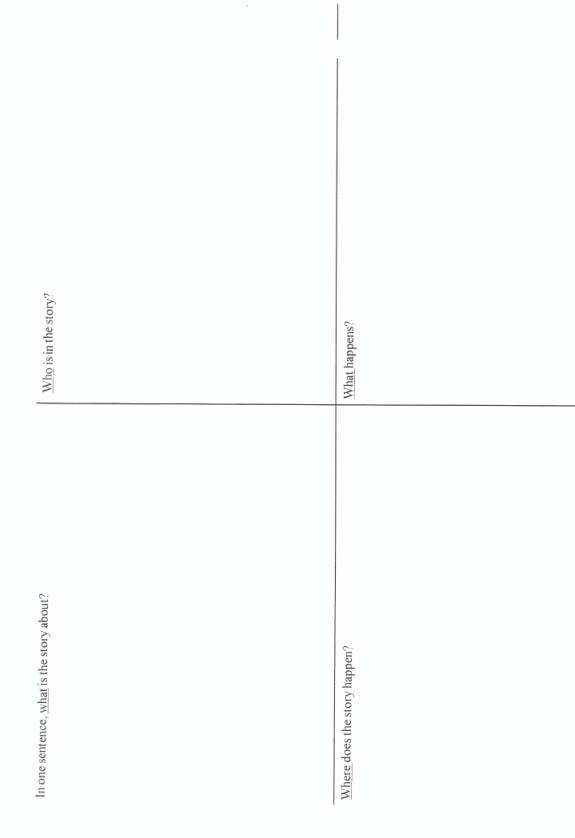

Story Maps

Story maps are typically used with fiction

material. When reading a short story or

book a story map may be completed after you have finished reading. Longer books may need story maps completed

at the end of a chapter or after several chapters.

Story maps may ask students to give information about

the characters, name and description, and the setting, where and when. Story maps provide a place for students to

record the main events of the chapter in the order in which they took place. Students may include illustrations and/or

written descriptions.

There are many types of story maps; below is an example

of a completed map. The Appendix has

sample story maps that you may choose to use with your students. Talk with the

teacher you are working with to see if he/she has a preference of which story

map to use.

Diagrams

Diagrams may be used with non-fiction materials. Diagrams must include a caption and

labels for the illustration. Students

may refer to diagrams in reference materials to help them understand the parts

of a diagram.

If students have read how blood flows through the heart they could draw a diagram of the heart, with the parts of the heart labeled, and show the path blood follows as it goes through the heart. Below is a sample diagram of how an atoll is formed; notice that the diagram has a title and the pictures have an explanation.

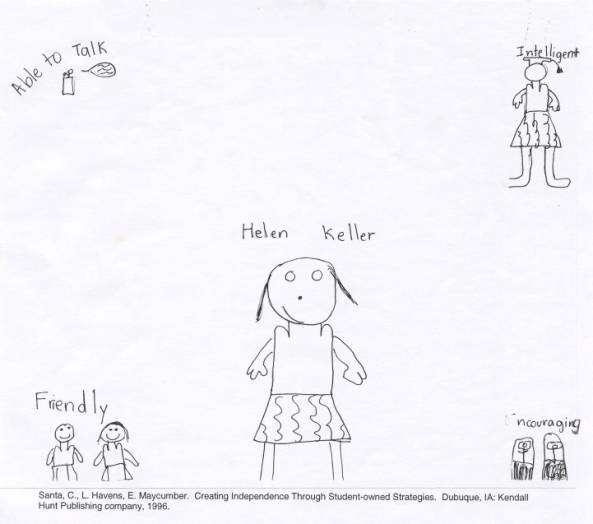

Character Maps

Character maps may be used with

fiction or biographical / auto-biographical text. In the center of the paper students draw the character, then

around the character pictures are drawn that describe the character. Beside each picture is a word or phrase that

tells the characteristic being illustrated.

The character map can be added to after reading a chapter or several

chapters. Sometimes throughout a book a

character will change, if this happens you may want students to draw a second

character map with the new characteristics.

Then by placing the maps side by side students can see the change in a

character.

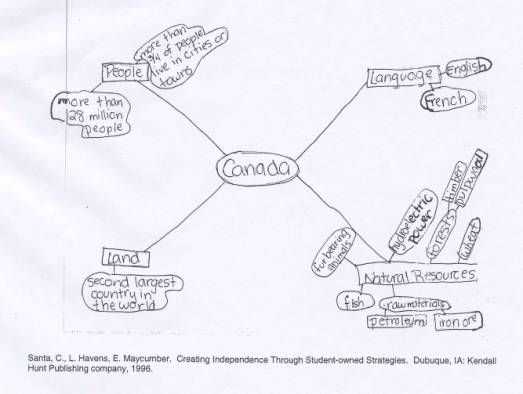

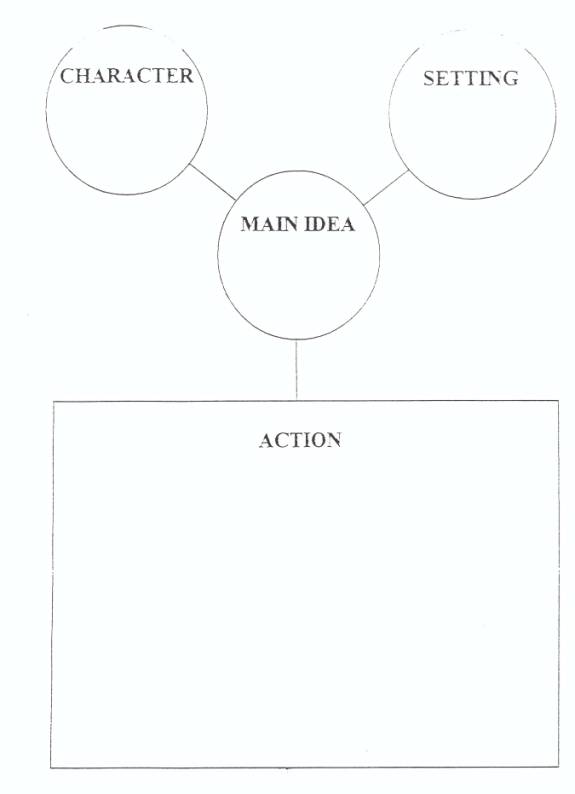

Concept Maps

Concept maps are a pictorial representation

of the relationship among ideas.

Mapping works well to help students organize information and ideas.

1. Before

reading choose a word or concept that relates to the topic and write it in the

center of the map.

2. Have

students brainstorm what they know about the topic. List their ideas on a separate piece of paper.

3. With

the students categorize the information from the brainstormed list and place

the categories around the topic.

4. Place

the ideas from brainstorming into the appropriate categories.

5. Read a part of the selection or all of the selection and add new information to the map. New information and/or concepts can be added as students are reading or after reading is completed.

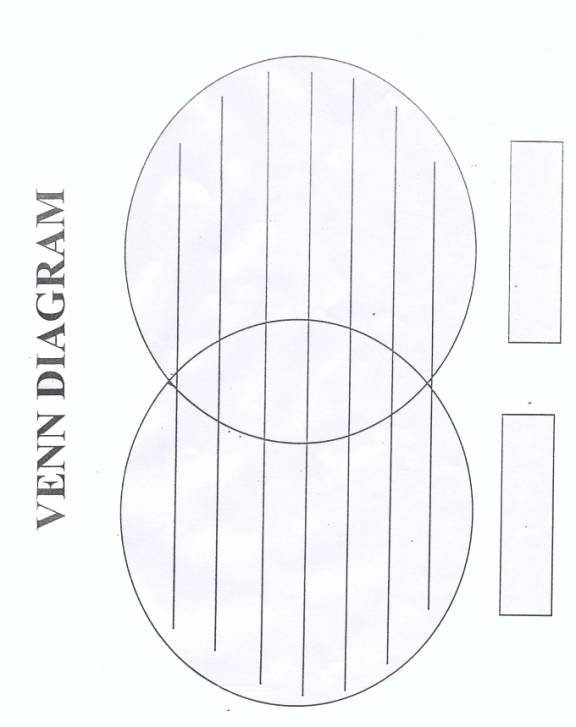

Venn Diagrams

A Venn Diagram is a structure that

shows how 2 topics are related through their similarities and differences. Characters, settings, stories, ideas, and

topics may be used with a Venn Diagram.

To make a Venn Diagram draw two circles with an area of overlap. The overlapped area is where similar traits

are to be recorded. The area of the

circle not overlapped is where the traits that are different are recorded. This organizer may be used as a post-reading

activity.

A blank Venn Diagram is provided in the Appendix.

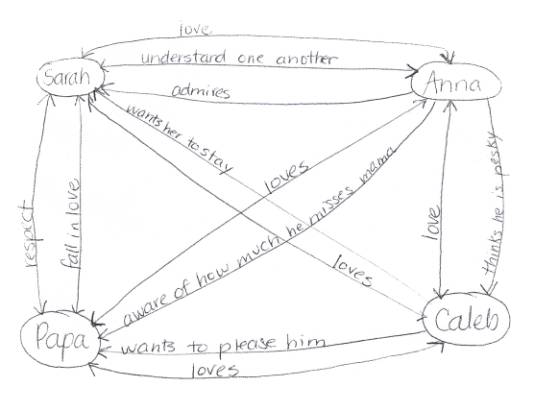

Sociograms

Sociograms are used to show relationships among

characters. On a sheet of paper record

the names of the main characters with a circle around each name. Then choose two characters and ask students

to tell how the characters feel about one another or relate to one

another. Draw a line between the two

characters and on the line write a word or phrase that describes the

relationship. If the description

describes the way both characters feel, draw arrows on both ends of the

line. The example at the bottom of the

page shows that Papa and Sarah respect one another, so an arrow is drawn at

both ends of the line. If the

description is appropriate for only one of the characters, then an arrow is

drawn to show which character has that feeling. Below, Anna feels that Caleb is pesky, so at the end of the line

an arrow is drawn just for Anna.

You may want to assign a color for each character; and when you draw an arrow for that character, use his/her color. You may also want to use color to show the change in a relationship over time. In the example below, Sarah and Papa had respect for one another at the beginning of the book, so the line could have been drawn in blue. At the end of the book Sarah and Papa have fallen in love, this line could have been drawn in red.

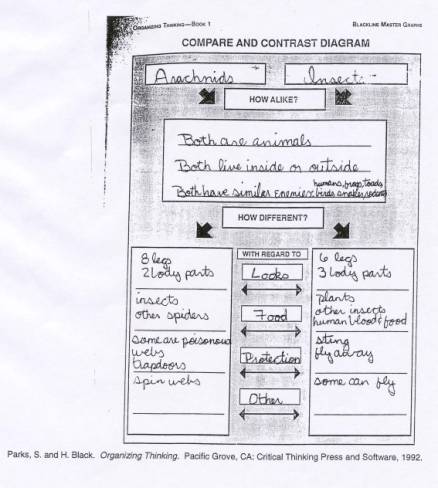

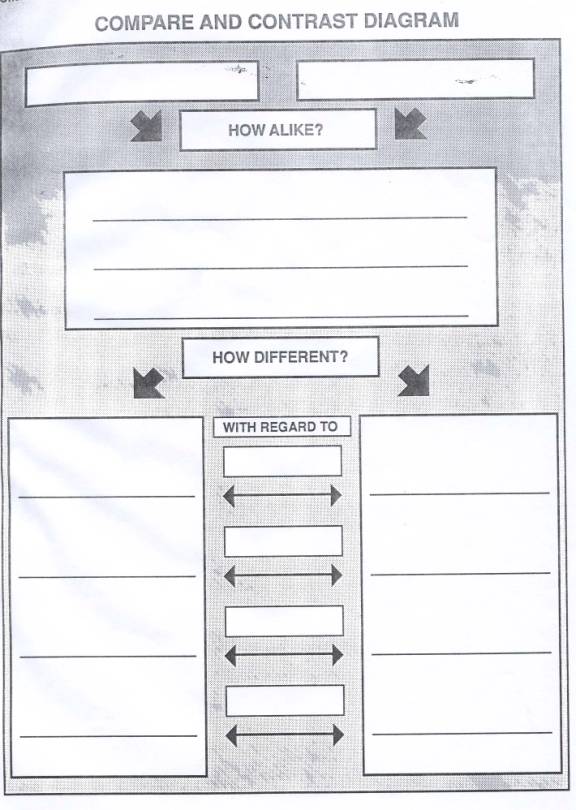

Compare and Contrast Diagram

1. After

reading choose two concepts or characters and write them in the blanks at the

top.

2. Then

have students record phrases which show the similarities in the "How

Alike" box.

3. In

the "with regard to" section write the quality being compared. This section is to be completed by the

tutor, not the student.

4.

Record

phrases that tell the differences in each "How Different" box.

A blank Compare and Contrast Diagram is in the Appendix.

DISCUSSION

STRATEGIES

Discussion Strategies

One of the most challenging tasks a tutor will face is

involving ALL students in the discussion of the text. It is important that everyone has an opportunity to share his or

her answers, thoughts, and opinions.

The following strategies are suggestions of ways to involve all students

in a discussion.

Rally Robin

This strategy allows students to work in pairs and take

turns talking. Assign each student a

letter A or B. After asking a question,

tell student A he/she will begin the Rally Robin. Student A will make a statement, then student B would

respond. This sequence continues until

you call time. If you have four

students, you would have 2 pairs talking simultaneously.

Rally Table

This strategy is designed like Rally Robin, but instead

of talking the students take turns writing.

This would work well as a pre-reading strategy. If you were reading about the landforms of

Africa and you wanted to see what the students know about this topic, ask

student A to start the list and add one thing he/she knows. Then student B would write. Students would hand the paper back and forth

until you called time.

Round Robin

This strategy involves all the students in a group

sharing with one another. In a Round

Robin discussion all students must respond and listen. If you are discussing a character in a

novel, ask the group to Round Robin discuss why they think a character behaved

in a certain manner. The discussion

would begin with a chosen student, the student on his/her left would respond

next, and this would continue until you called time. The discussion could go around more than once. While a student is talking, no other student

may comment or ask a question until it is their turn.

Round Table

This strategy is like Round Robin, but instead of

answering orally students will write.

Your group has just finished reading about Canada and you want to see

what they remember. Give one student a sheet of paper. Tell the students you want each person to

list one thing they remember from the reading selection, but they cannot write

what someone else has written. The

first person writes one thing and hands the paper to the person on the left. The rotation continues until you call

time.

Think Pair

Share

After asking a question have students think about a

response. After 30-45 seconds of think

time ask students to share with a partner their response. Then the pairs can share with the entire

group.

Numbered

Heads Together

Assign each student a number, if you have 3 students use

the numbers 1, 2, and 3. After asking a question have the students huddle to

discuss the question to make sure all students can respond. Call out a number and have that student

respond.

APPENDIX

References

Graves, M. and B.

Graves. Scaffolding Reading Experiences. Norwood,

MA:

Christopher-Gordon

Publishers, Inc., 1994.

Morris, Darrell. Case Studies in Teaching Beginning Readers:

The Howard Street

Tutoring Manual.

Boone, NC: Fieldstream Publications, 1992.

Parks, S. and H.

Black. Organizing Thinking. Pacific

Grove, CA: Critical Thinking

Press

and Software, 1992.

Santa, C.,L. Havens,

E. Maycumber. Creating Independence

Through Student-

owned Strategies.Dubuque,

IA: Kendall Hurt Publishing Company, 1996.

Thonpson, Max and J.

Thomason. Learning Focused K-5 Schools: A

High

Achievement Project. Boone, NC: Learning Concepts, Inc., 1996.